A Short History of the Encaustic Tile

Chris Blanchett, Tile Historian

In the 13th century, no self-respecting Abbey, Monastery or Royal Palace would have been without its tiled floors. The earliest examples such as those still extant at Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire were made of variously shaped interlocking tiles of different colours, much like a mosaic, but these were difficult to make and even more difficult to lay and they rapidly disappeared in favour of inlaid or ‘encaustic’ tiles.

Encaustic tiles were made by impressing a pattern in the unfired clay to a shallow depth using a carved wooden mould. The resulting indentations were filled with a liquid clay, or slip, of contrasting colour. The tile body was usually of red clay with a white slip pattern. The tiles were glazed with a simple lead glaze made by boiling up scraps of lead (often from roofing or window making) and skimming off the lead oxide which formed on the surface. This was powdered and mixed with water and possibly some form of gum to make it adhere to the tile surface. When fired in a wood burning kiln to about 1000ºC, the glaze melted and formed a thin skin over the tile. Impurities in the glaze gave a warm honey tone to the white clay inlays and a deep rich brown colour over the red body.

By the 16th century, the fashion for inlaid tiles had passed but in the early years of the 18th century, architects began to look to the past for inspiration and came across examples of the old medieval tiles. Several authors collected the designs found on such tiles and published them, leading to an interest in and demand for reproduction tiles for new and renovated church floors. The Gothic Revival had begun.

In 1835, Samuel Wright, a Merchant in Zaffer (raw cobalt ore that was used in the pottery industry to create an intense blue) from Stoke-on-Trent experimented in making reproductions using plaster and steel moulds, but due to the nature of his business decided to sell the rights to his patent to Chamberlain & Co of Worcester and Herbert Minton in Stoke in equal shares. Chamberlain started production immediately, but Minton decided to further refine the process, building a special small kiln for his experiments. Initial results were disappointing; the local clay from the Stoke area shrank alarmingly on firing and the inlaid pattern continually came away from the body of the tiles. He kept on however and in 1842 was ready to supply his first major commission for the Temple Church in London. He collaborated on this project with the architect, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin who was also working on the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) in London and soon Pugin was specifying Minton tiles for the Palace and many other prestigious projects at home and abroad.

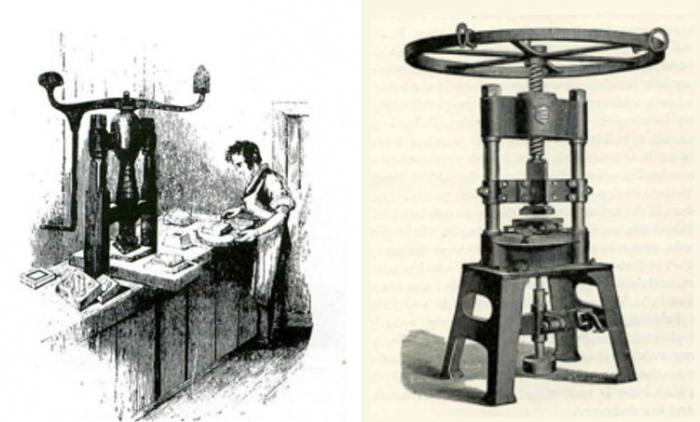

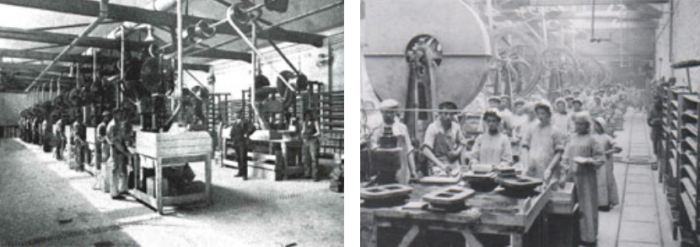

As encaustic tiles became more and more popular for churches, public buildings and even humble homes, several other manufacturers started production, the most famous of these being William Godwin of Lugwardine, Hereford. Godwin made tiles with a rather more authentic medieval feel than the mass produced Minton tiles and achieved considerable success with architects for church restoration. In the 1860s, they experimented with a more mechanical form of tile production, dust-pressing. This involved drying the clay to about 8% moisture content when it becomes a powder or ‘dust’. This was then compacted in a steel die using a screw press, initially hand-powered but later operated by steam.

Dust-pressing had been developed for making wall and plain floor tiles in the 1840s, following an 1842 patent taken out by Richard Prosser. In the 1860s, Godwin collaborated with William Boulton, a press manufacturer, to create inlaid floor tiles by a similar process and in 1868, Boulton patented the first machines capable of making dust-pressed encaustic tiles. The system was complicated and employed separate fretted brass plates for each colour. However, using the new machinery, Godwins were able to produce tiles with up to 8 different colours of clay!

On the continent, a slightly different technique was used involving a ‘laiton’ or frame of thin metal which was placed into the die, each compartment of the frame being filled with a small amount of different coloured dust clay.

The frame was carefully removed, the backing clay added and the whole lot pressed under huge pressure – up to 4 tonnes per square inch. This gave a compacted tile which could be handled easily and fired straight away. The pressing of the clay forced the separate colours together giving a softer edge to each colour than the British process.

By 1900, there were hundreds of makers across western and southern Europe and although encaustic tiles fell out of favour in the UK, large -scale production continued in France, Belgium and Spain right up to the 1930s. In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in encaustic tiles and many of the original floors are now being carefully removed, restored and re-laid in modern and period homes. After up to 100 years of wear, they still retain their full beauty and are a tribute to the craftsmen who produced them.

'Carreaux de ciments'

Carreaux de ciments tiles were also manufactured by hand and were popular in France around 1890-1910, providing a lower cost option to the more refined and expensive ceramic encaustic tile. Instead of using clay, a base of cement was laid in the mould and different coloured cements, often mixed with marble dust, were poured into the patterned sections of a brass mould placed in a wooden block, thus producing the pattern of the tile. Once removed from the block, instead of the tile being fired in a kiln as is the case with ceramic tiles, the tiles were left to 'cure' or dry slowly, often in a carefully maintained humid room. This allowed the cements to not only set properly but the controlled humidity ensured no small fissures appeared on the surface of the tile.

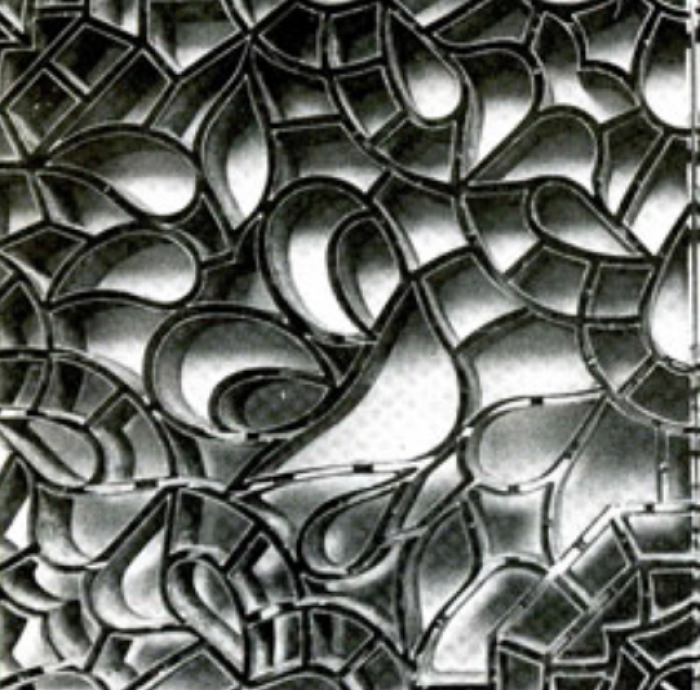

Antique carreaux de ciments tiles were typically larger than antique ceramic tiles, being commonly 17cm or 20cm sq compared to c.14cm to 17cm sq for ceramic tiles and were usually a third to a half thicker too making them obviously heavier. A 20cm square tile can weigh as much as 2kgs. The material used also influenced the tiles pattern as carreaux de ciments tiles could only accommodate a colour element in the design no smaller than 5mm in width, whereas ceramic tiles, owing to the finer dust clays and slips used, could accommodate design features like lines or framing as small as 1mm wide. Designs were therefore much less ornate, catering for more a purer and often classical tessellation. The two tiles below provide a good example of a more ornate, detailed ceramic tile and a less ornate and classical carreaux de ciments.